Boats

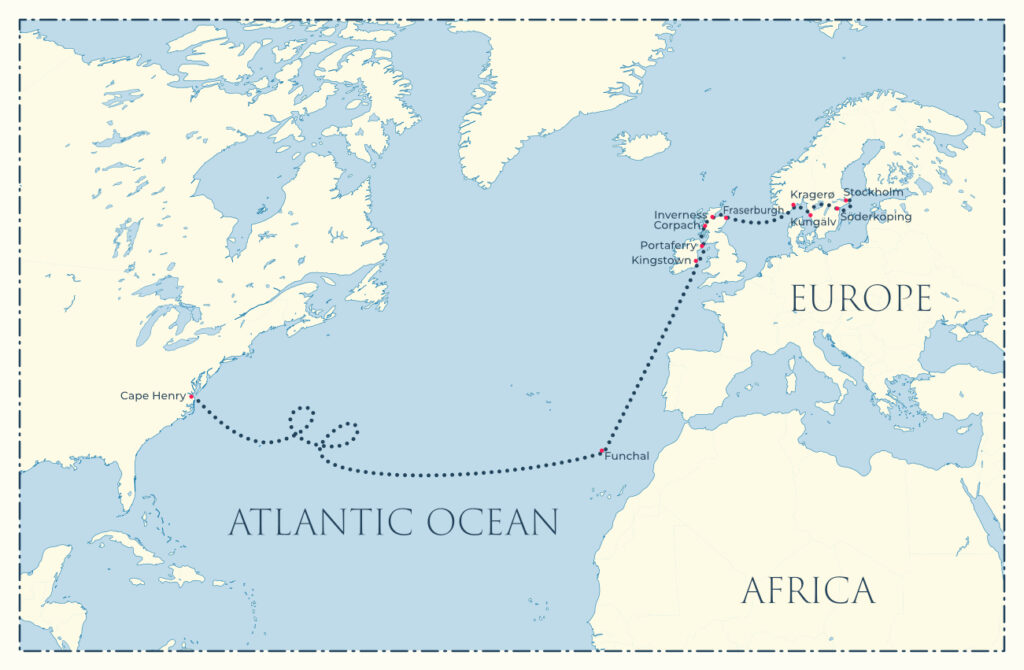

From Sweden, most of the Viking boats sailed around Norway and Denmark and stopped in Scotland and Ireland and sometimes England before heading south across the Bay of Biscay to Spain and the Madeira islands. From there, the boats took advantage of trade winds to sail to North America. This map shows a general route, depicting storms in the Atlantic that almost capsized several ships.

JOURNEYS TO UNITED STATES

For refugees fleeing communism after World War II, America stood out as a beacon of hope as “the land of the free.” The United States—unlike Sweden—had refused to recognize the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states in 1940 and diplomatic representations in exile continued operating until independence was restored in 1991. Ernst Jaakson, the legendary consul general in New York, actively advocated on behalf of the postwar refugees in America.

The first Viking boats to land in 1945 galvanized popular support for the brave sailors. America was already familiar with Kõu Valter, the captain of the Estonia, because in 1930 he and his brother Ahto sailed across the Atlantic in a 26-foot (8 meter) sailboat and became media celebrities. The Erma, a 37-foot (11.2 meter) sloop, arrived next, completing a journey immortalized in Sailing to Freedom. This 1952 novel, coauthored by passenger Voldemar Veedam, became an international bestseller translated into 30 languages.

Despite public admiration for the brave sailors, nearly all of the refugees spent months on Ellis Island in New York before successfully petitioning to immigrate. Passengers on the Edith were refused entry and after months on Ellis Island, were sponsored by the Lutheran Church of Canada to settle in Canada.

The arrival of the refugees helped trigger a debate on U.S. immigration. Quotas set in 1924—124 Estonians, 142 Latvians, and 344 Lithuanians were admitted annually—were inadequate for the post-war era. With the Cold War fanned by McCarthyism, the dramatic stories of refugees fleeing communism and risking all to live in freedom helped usher in changes in immigration legislation.

President Harry S. Truman’s 1948 Displaced Persons Act opened the doors of America for 400,000 post-war refugees, making it possible to immigrate legally and ending one of the drivers behind the desperate Viking boat journeys. Additional legislation supporting immigration followed and between 1948 and 1952, about 12,000 Estonians entered the United States.

The crew of the USS John P. Gray waving farewell to the Erma. The Navy transport ship spotted the tiny boat just as it was running out of critical supplies and provided aid.

Boat name/Date of arrival/Passengers/Destination

- Estonia December 1945 6 Miami, Florida

- Erma December 15, 1945 16 Little Creek, Virginia

- Inanda August 21, 1946 18 Miami, Florida

- Brill September 9, 1946 12 Miami, Florida

- Linda September 28, 1946 18 Miami, Florida

- Edith September 15, 1947 24 Savannah, Georgia

- Docan October 1, 1947 8 Miami, Florida

- Svea October 26, 1947 24 West Palm Beach, Florida

- Gundel July 20, 1948 29 Boston, Massachusetts

- Roland August 18, 1948 15 Southport, North Carolina

- Prolific Sept. 20, 1948 69 Wilmington, North Carolina

- Eeva January 21, 1949 37 Miami, Florida

- Parita April, 1949 43 Baltimore, Maryland

- Skagen July 5, 1949 16 Boston, Massachusetts

- Måsen August 29, 1950 108 Boston, Massachusetts

- Aura July 1951 3 New York, New York

- Walprio October 4, 1951 11 Fort Pierce, Florida

TOTAL 457 passengers

Sources: Baltimore Sun, March 3, 1950; Välis-Eesti, October 7, 1951; Eestlased Kanadas, Canadian Estonian Historical Commission (1975); Estonians in America 1945-1995: Exiles in a Land of Promise, Estonian American National Council (2016); “The formation and development of the Estonian diaspora,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (2010). Images reproduced with permission from the Estonian Maritime Museum.