Boats

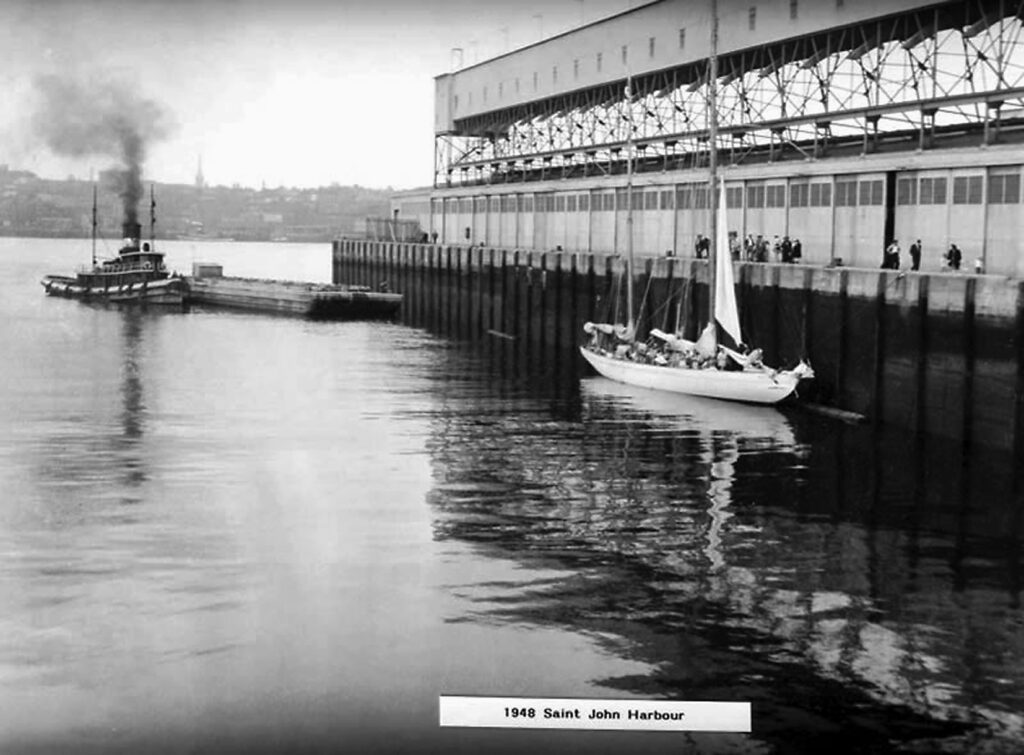

The Atlanta in Saint John harbor.

Atlanta

The Atlanta was the second refugee boat to reach Canada. It began its journey in Lysekil, Sweden, on June 19, 1948, with 42 Estonians on board, including four children. Two months later after a 6,000 mile journey (9,700 kilometers), the 86-foot-long (26 meters) two-masted luxury ketch docked in Saint John harbor, New Brunswick, on August 19, 1948.

Kalju Pullerits, who organized the voyage, purchased the 60-ton yacht in autumn 1947 for 70,000 Swedish kronor (35,000 Canadian dollars). The boat had been built in Sweden in 1898 and was used by the Swedish youth sea cadets for training. Each refugee paid 4,000 kronor for passage, which included food and other expenses on board. The Atlanta’s captain was Eugen Kommissar, an experienced seaman who had graduated from the Tallinn Maritime School’s 1944 class of master mariners.

Swedish officials authorized the Atlanta to leave Lysekil on a “pleasure cruise.” Passengers were allowed to bring two suitcases each and they carried medical certificates but no Canadian visas. On June 19, the journey began in sunny weather but after a couple of days the boat sailed into a storm and had to seek shelter near Kristiansand in Norway. On June 22, the yacht set off again, but had to maneuver around an uncleared minefield and got tangled in miles of fishing nets. On June 29, it reached Portland Royal Naval Base in Dorset, England. Captain Kommissar was familiar with the base because Estonian submariners had trained there in 1937.

On July 7, the Atlanta headed south, crossed the Bay of Biscay without incident, sailed down the Spanish and Portuguese coasts, and on July 13 sailed southwest toward the Canary Islands. The yacht arrived in Las Palmas on July 18 but was not allowed to dock, so merchants brought fruit and water to the ship. On July 19, the Atlanta began its long journey across the Atlantic, following the tradewinds route of Christopher Columbus 500 years earlier.

Passenger Elise Lige recalled the journey in a 1985 interview: “The waves were as high as a [tall] building, the ocean and sky seemed endless and lasted for weeks. During clear, warm nights the sky was star-studded, and the water glittered like diamonds. People slept on deck or not at all. The sunrise was equally gorgeous and another morning treat were the dolphins and schools of fish passing by.” At one point, Elise Lige averted tragedy by catching Ernst Laur by his feet as he went overboard while filling a bucket of water.

By the time the yacht reached Bermuda, one of the water tanks had sprung a leak and run dry. Captain Kommissar decided to sail to Bermuda to get more water, however the crew did not have accurate nautical charts of the area. The Atlanta ran aground on an underground reef but was saved by a storm that rocked the boat free. With sharks circling the boat, the passengers decided to forgo Bermuda and sail to Saint John harbor, which the captain had previously visited. Despite strong winds and high waves, sailing conditions were generally favorable. To cope with the lack of drinking water, passengers collected rainwater that ran down the sails, and in pots and pans during heavy downpours.

On August 19, the Atlanta arrived in Saint John. The Canadian coast guard assumed there were rich American tourists on board until they met the hungry, thirsty, and sunburned Estonian refugees. They were taken ashore and spent a month having medical and security checks at Lancaster Hospital. While in detention, some passengers like Kalju Pullerits received deportation orders that were later rescinded. In 1995, he wrote a letter about his experience:

“My university studies were interrupted by war, and we were penniless when we arrived in Saint John. Immigration Authority issued deportation order with statement that we would be most likely in public charge and did not have sufficient funds to support ourselves. While Atlanta was still in the harbor, we prepared for the departure to Argentina since return to the country of birth, by the rule of the immigration, meant certain death to all of us. Finally, we were accepted and allowed to stay and we traveled by train, paid by Canadian Red Cross, to Montreal and most of the boat family to Toronto.” [Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21]

Eventually, the Canadian government admitted all the passengers on the Atlanta.

What happened to the Atlanta?

The Atlanta was sold to a Saint John businessman for 5,000 Canadian dollars, a fraction of the 35,000 Canadian dollars the Estonian shareholders had paid for it. The yacht, however, was not maintained properly and ended up beached in Indiantown, New Brunswick. In 1964, Canadian boating enthusiast Don Hartt bought the wrecked hull, restored it, and sailed it around the Caribbean. In 1975, it was sold again, and the new owners brought it to Toronto, where 21 of the Estonian refugees reunited on board. The yacht began making day cruises around Toronto but, in the summer of 1976, it crashed into an underwater shoal near Kingston harbor and eventually was towed to shore as a battered wreck.

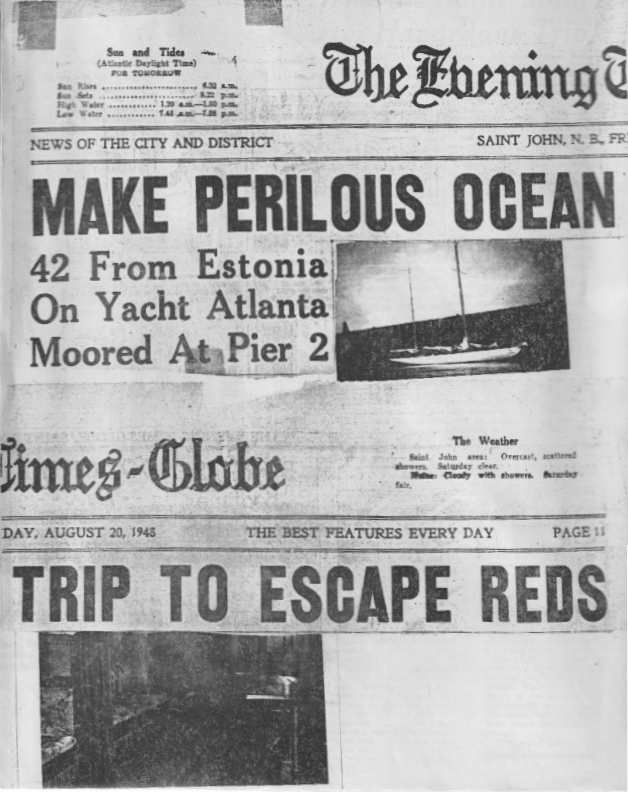

“Perilous Ocean Trip to Escape Reds”, The Evening Times-Globe, New Brunswick, Canada, August 20, 1948

Known crew and passengers:

- Captain Eugen Kommissar, 32, Maimo, his wife, and their daughter, Malle

- Kalju Pullerits from Karula and Aino, his wife, from Tallinn

- Andrei Vool from Häädemeeste

- Alfred and Adele Kelberg from Hiiumaa

- Siegfried Polli from Koita and Nadja Aste from Kuressaare

- Valentin Aas from Hellamaa and Elise Pauli from Kuusalu, and their son, Ivo

- Leida Rohtla from Albu

- Elmar and Leida Huberg, and their son, Peet, from Haapsalu

- Karl Aaspere from Tallinn

- Adele Kask from Puurmann

- Marta Sepp from Kaarma

- Anastasia Sepp from Saaremaa

- Vladimir Sepp and Tarmo, his son, from Saaremaa

- Ernst Laur from Allik

- Leonard Aidamets from Saaremaa

- Lydia and Victor Sild from Võisikt

- August Nõmme from Tila

- Arved Liideman from Paikus

- Priidik Seppel from Haapsalu

- Julia Viilu from Saaremaa

- Rudolf Müid from Emmaste

- Evald Engman from Noarootsi

- Leander and Ella Üksik from Noarootsi

- Erika Nõmme from Narva

- Edvard and Helme Kaju from Emmaste

- Pauline Eigi from Haapsalu

- Arnold Pflug from Tapa

- Arnold Rae from Virumaa

- Silvi Sadul from Hiiumaa

- Elise Lige

Photograph reproduced with permission from the Estonian Maritime Museum.