Boats

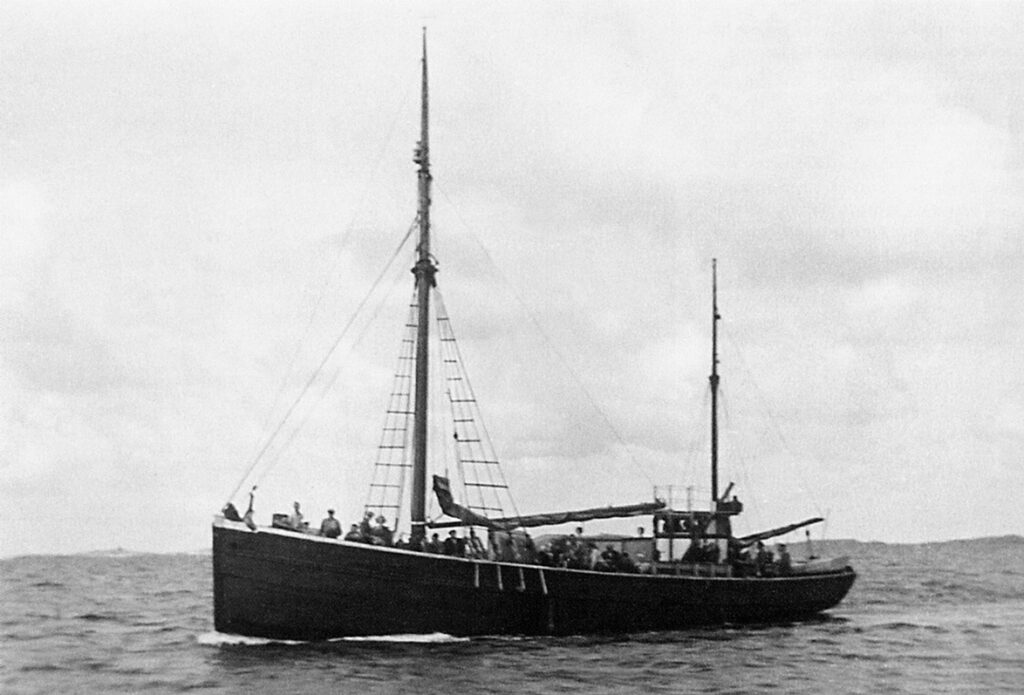

The Prolific’s long journey begins.

Prolific

The Prolific left Uddevalla, Sweden, on July 23, 1948, with 69 passengers. It arrived a month later in Wilmington, North Carolina, having survived a hurricane near the Bahamas that almost capsized it.

This Viking boat journey stands out because several passengers recorded their experiences. Enn Kalde kept a diary. Ruth Oja-Sootaru recorded her experience for Kogu me Lugu. Ants Lepson painted the boat’s dramatic moments and his brother, Indrek, wrote down his memories. Argosy magazine published a colorful account by Carl B. Wall, who would go on to co-author Sailing to Freedom, the 1952 bestselling book about the Erma.

The Prolific was a wooden 72-foot-long (21.2 meters), two-masted schooner built in 1891 in Grimsby, England. In 1898 it was sold to a Swedish shipping company and used for fishing until the refugees pooled their savings to buy it. The group moved to Uddevalla and slept on board as they prepared for the long journey.

The Prolific was a wooden 72-foot-long (21.2 meters), two-masted schooner built in 1891 in Grimsby, England.

On July 23, Captain Abrahamsson, the former owner, piloted the boat as far as Fotö, ordering most of the passengers below deck to avoid unwanted attention. The first captain hired by the refugees had suddenly quit, saying, “To take so many people to sea in a rotten boat like this is criminal.” Two Finns joined the boat instead.

Before reaching Dover, England, on July 27, Enn Kalde wrote: “Yesterday we saw the first dolphins. These large fish with blue-gray backs swam right next to the ship, their big fins visible as they jumped between the waves. At night in the moonlight, the sea glitters with phosphorous as though handfuls of glowworms had been dropped into the foaming waves in front of the ship.”

The ship’s littlest refugees in the middle of the Atlantic.

The Prolific stopped in Dover on July 29 to replenish supplies, docking near the Ilmarine, which was headed to Argentina. The boat then sailed south toward the Bay of Biscay, “the grave of seamen,” and into a storm. As the boat floundered dangerously, a three-masted Spanish schooner appeared, signaling the boat to follow it to safety in Marin, Spain. Local residents welcomed the visitors and helped repair the boat. Four days later the Prolific left, headed south, and began crossing the Atlantic.

On August 18, the Prolific reached Funchal, Madeira. Locals had already encountered other refugee boats and treated the passengers well after they learned they were fleeing communism. The Prolific set off a week later and by September 8, it had passed the halfway point across the Atlantic. The weather was very hot, and all 10 children caught chicken pox.

Drying out after the hurricane.

Four days later, the Prolific found itself in the middle of a hurricane. At one point, the crashing waves grew very loud and everything went silent—the ship was completely under water. But slowly it rose to the surface. Realizing the boat might sink, a passenger list was stuffed into a bottle and thrown overboard. Ruth Oja-Sootaru recalled that she wanted her young daughter, Helgi, to die first so she wouldn’t look for her mother.

Captain Berndt Andersson stayed at the ship’s wheel for 48 hours—and kept the Prolific afloat. The hurricane blew the ship off course, so instead of heading for Florida, it found itself further north.

On September 20, the Prolific’s passengers spotted land, and the next morning the U.S. Coast Guard guided the boat to Wilmington, North Carolina, where the Roland had docked a month earlier.

The Prolific and Roland’s passengers were interned together on Ellis Island in New York for several months until the Lutheran church found sponsors. Positive press coverage, including stories that compared the Prolific to the Mayflower, aided the refugees’ quest to stay in America. On August 15, 1951, President Harry S. Truman signed a private bill legalizing entry for both groups. Within three years, many of them had become U.S. citizens.

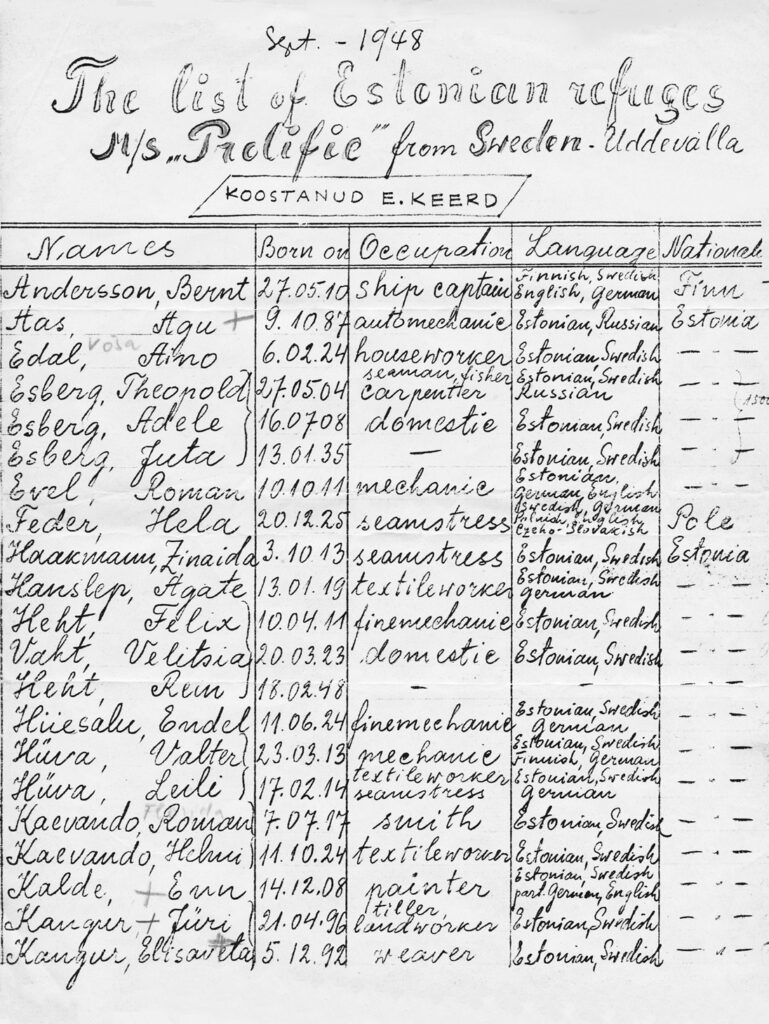

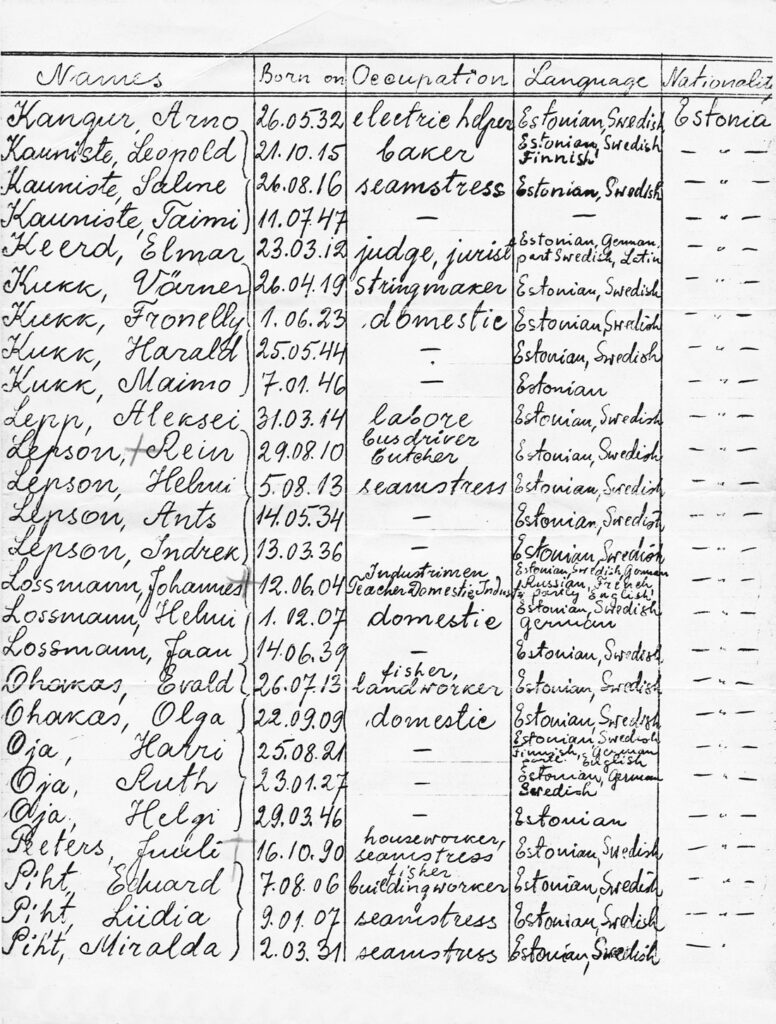

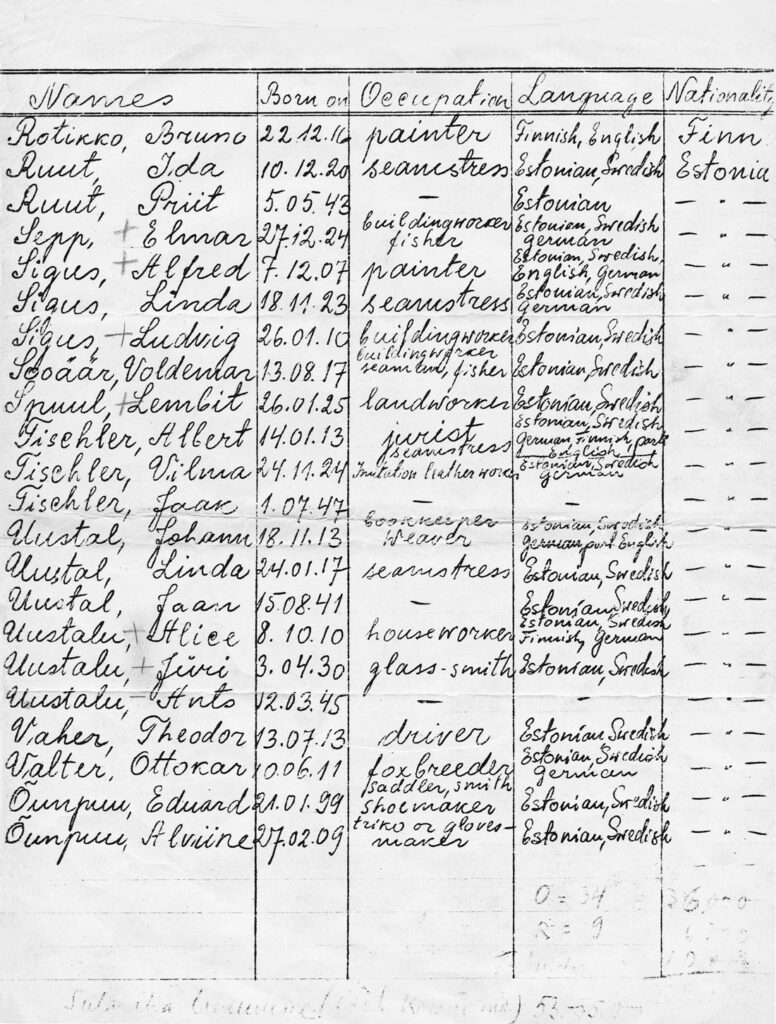

The Prolific’s passenger list was stuffed into a bottle and thrown overboard during the hurricane.

TIME magazine coverage

On October 11, 1948, Time magazine published, “Refugees: Outward bound.”

“Wherever you are, we will get you.” These words, beamed to Sweden over the Soviet-controlled Estonian radio, haunted the memories of a 21-year-old housewife and her friends seeking entry into the U.S. last week. They were the leitmotif of a journey that had seemed endless. “I fled from Estonia to Finland because of the Germans,” said the girl, on Ellis Island. “A year later, in 1944, I fled from Finland to Sweden because of the Russians.” Her shipmates—steelworkers, a glassblower, weavers, seamstresses, mechanics, lawyers, farmers, fishermen—had similar tales to tell. An Estonian farmer told how his 76-acre farm had been seized when the Russians decided he was a kulak. A girl remembered the sight of three boys, their eyes pierced, their fingers cracked, their hair torn out for resisting Russian conscription.

Sixty-nine refugees who feared that the Russian threat might reach into Sweden for them crowded into the Prolific, a blunt-nosed fishing schooner, about half as big as the Mayflower. They had sailed over 6,000 miles of ocean to reach a U.S. haven. They had weathered storms in the Bay of Biscay and off Cape Finisterre. They had traded their clothes for grapes and coconuts in Madeira and broken their steering gear in a hurricane off Bermuda. Under leaky hatches in fetid, 90° heat, their women had nursed children sick with chicken pox. After 60 days at sea, they had put in at Wilmington, N.C., and been shipped by train to New York.

Since 1945 more than 230 Baltic refugees have come to the U.S. in cockleshells even smaller than the Prolific. The Estonia, which brought Kõu Walter and his wife and children to Florida, was only 47 feet long. The Erma, which sailed from Stockholm to Little Creek, Va., charting her course on a standard schoolboys’ map of the Atlantic, measured 37 feet.

Most of the passengers of the first five boatloads to arrive in the U.S. have been given visas, and many have taken out their first citizenship papers. Others have been paroled to the Salvation Army. So far, none have been returned to Russia, and, though immigration officials are reluctant to say so, none are likely to be.”

The Prolific’s passenger list was stuffed into a bottle and thrown overboard during the hurricane.

The Prolific’s passenger list was stuffed into a bottle and thrown overboard during the hurricane.