Boats

Estonias passagerare framme i Miami. F.v. Mihkel Kõvamees, Kõu Valter med Helme, 4 månader, i famnen, hans fru Klarissa och deras döttrar Maia, 8, och Aloha, 9. Återpublicerad i Välis-Eesti juni-juli 1992.

estonia

Estonia var den första vikingabåten som korsade Atlanten och därmed inspirerade flera flyktingbåtar som senare skulle följa i dess fotspår på vägen från Sverige efter andra världskriget.

Den 10 juli 1945 lämnade tre rutinerade estniska sjömän, Kõu Valter, Mihkel Kõvamees och Bernhard Veskimester, Göteborg för att segla till England och sedan Amerika ombord den 11 meter långa segelbåten. Valters fru och tre unga döttrar var också ombord.

Kapten Valter var en välkänd seglare som hade korsat Atlanten redan 1930 tillsammans med sin bror, Ahto, på en 8 meter lång segelbåt. 1934 återvände han till Estland och tjänstgjorde i flottan. 1944 flydde han med sin familj till Sverige, och gjorde även två farliga resor till Finland med sin egen båt för att evakuera 964 estniska flyktingar därifrån till säkerhet.

England runt: Välis-Eesti rapporterade om Estonias transatlantiska resa under hösten 1945.

I juli 1945 satte Estonia ut från Norges kust, och hamnade direkt i en tuff storm på Nordsjön, som även knuffade ut båten i ett farligt minfält. Efter att ha lyckats undvika sjöminor i tre dagar fick besättningen syn på en norsk fiskebåt användande sina driftnät, vilket indikerade att de var utom fara, och de seglade därefter till Leith i Edinburgh, Skottland. Utländska fartyg tilläts inte att lägga till, men Estonias besättning fick lov att gå iland tillsammans med eskort för att köpa förnödenheter och sjökort. Den 27 juli tvingade höga vindar Estonia att söka skydd i Aberdeen. Bernhard Veskimeister, som senare skulle bli kapten ombord Ly, som seglade till Sydafrika 1948, lämnade gruppen och reste till London. Från Aberdeen seglade Estonia genom den Kaledoniska kanalen till den skotska västkusten.

Mihkel Kõvamees skrev i sin loggbok:

“I Aberdeen är det tydligt att folkets kläder har blivit mycket sämre under krigets gång. Det finns inte mycket att titta på i affärerna – de är tomma. Men om kvällen är tavernorna och barerna ännu mer fulla än de var förr i tiden, med folk som dricker öl och pratar.”

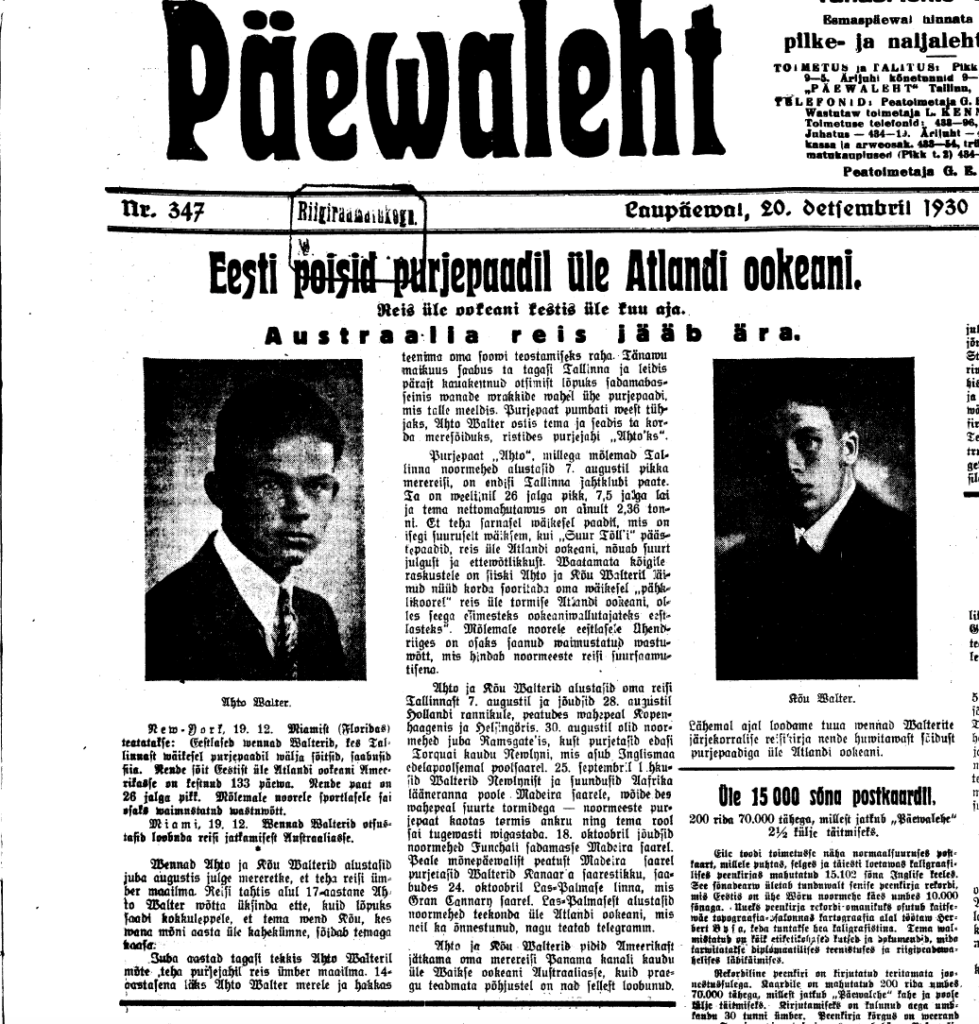

Kõu Valter och hans bror Ahto var erfarna seglare som redan hade korsat Atlanten ombord en liten segelbåt när de var 23 och 19 år gamla. “Estniska pojkar seglar över Atlanten”, Päewaleht, 20 december 1930.

Estonias utombordsmotor slutade fungera ute på Irländska sjön och besättningen såg till att reparera motorn vid ett stopp i hamnen i Newlyn, för att förbereda sig inför den långa sträckan över Biscayabukten, “Där alla världens vindar och strömmar möts, och sjömän alltid stöter på överraskningar,” skrev Kõvamees.

Den 13 september rapporterade han att vädret plötsligt blev tropiskt. En morgon fick gruppen syn på vad som såg ut att vara en tunna i vattnet, men det visade sig vara en sköldpadda som försökte klättra upp på ett runt föremål av järn. Kapten Valter ville fånga djuret och göra sköldpaddssoppa men insåg sedan att föremålet kunde vara en gammal mina. “Vi lämnade sköldpaddan att kämpa vidare, och vi var alla ledsna,” skrev Kõvamees.

Den 20 september nådde Estonia Funchal, den största hamnen i Madeira, där de omgavs av handelsmän i båtar som ville byta portugisiska varor mot klädesplagg, som det fanns brist på.

Innan de lämnade Madeira den 10 oktober fick männen reda på att kapten Harri Paalberg var på väg ombord Erma, en 11 meter lång slop, och de lämnade ett brev med hälsningar. Efter det satte Estonia kurs mot Amerika, framförda av en nordöstlig passadvind.

På Madeira: Välis-Eesti fortsatte sin rapportering om Estonias transatlantiska resa under hösten 1945.

“Med en 4000 mils sjöresa framför dig snurrar ditt huvud,” skrev Kõvamees. “Det var alltid tydligt för oss att denna resa skulle vara en stor risk. Men du måste alltid hoppas på det bästa, och det var det vi gjorde.”

Den 6 november tog passadvindarna slut, och luften blev varm och kvalmig. “Vi svettades ymnigt, vilket i sin tur gjorde oss törstiga och minskade på våra vattenresurser. I Madeira fyllde vi på våra vattentankar med ett och ett halvt ton vatten, och bestämde oss för att endast använda det för mat och dricka. Vi gav upp alla andra behov. På en segelbåt är det vattnet som håller igång besättningen.”

Vädret på Atlanten var fördelaktigt största delen av resan, och den 20 november 1945, fyra månader efter att de lämnat Sverige, anlände Estonia till Miami, Florida. Ahto Valter, som bodde nära Miami, hjälpte gruppen eftersom de saknade inresevisum. De använde sina svenska flyktingpass fram tills att de amerikanska tjänstemännen fick veta att de hade estniska pass utfärdade i London. “Det finns inga bättre pass i Amerika,” hävdade de. Kõu Valter och hans familj slog sig ner i Florida. Kõvamees arbetade som en långdistankapten med utgångspunkt från Amerika i nio år innan han återvände till Sverige.

Besättning och passagerare:

- Kõu Valter, fru Klarissa och döttrarna Aloha, 9, Maia, 8, och Helme, 4 månader

- Mihkel Kõvamees

- Bernhard Veskimeister (gick av båten i Skottland)