Free winds

After World War II, Estonian refugees in Sweden escaped in small boats across the Atlantic. Discover how and why they risked all to live in freedom.

free winds

In 1945, the Erma, a 37-foot sloop, carried 16 Estonians across the Atlantic to America. Their journey is told in Sailing to Freedom, which became an international bestseller.

This exhibition highlights the extraordinary voyages of thousands of Estonians who secretly fled from Sweden in the late 1940s and sailed in old, battered boats across the Atlantic Ocean to freedom.

The refugees had already escaped once from their homeland. In autumn 1944, as the Nazi German occupation collapsed at the end of World War II and the Soviet Army advanced across the Baltic states, tens of thousands of Estonians crowded into small boats and fled to Sweden. The refugees thought they were safe but soon the Soviet Union began pressuring Sweden to send them back. Having survived the 1940-41 Year of Terror when Soviets imprisoned, murdered, and deported 20,000 Estonians, the refugees had no illusions about what would happen if they returned.

Preferring to control their destinies, Estonians pooled their savings, bought and repaired old boats, and sailed as far away as possible from the Soviet Union.

The ships sailed without modern communication equipment and crews spent days looking out for minefields and Soviet patrol ships in the North Sea. Captains navigated through storms in the treacherous Bay of Biscay relying only on antiquated maps and sextants. With diesel fuel in short supply, the boats took advantage of the Atlantic trade winds that carried Christopher Columbus to the Americas 450 years earlier.

The popular press dubbed the vessels “Viking boats” because they came from Sweden and because, thanks to their skillful crews, most reached their destinations. “No one, except the Vikings, has come in such a small boat,” an astonished Canadian official exclaimed when the Astrid landed in Quebec in 1948 with 29 people on board.

Between 1945 and 1951, about 47 ships left Sweden. At least 17 vessels made it to the United States, 11 reached Canada, 7 sailed to Argentina, 2 landed in Brazil, and 3 to South Africa. Estonians organized most of the unsanctioned voyages, but Latvians and other nationalities also captained and boarded ships. Several boats were forced to end their journeys early and others probably sank, but since the illegal voyages were planned in secret, accurate figures are unknown.

“Free Winds” is based on Jüri Vendla’s Unustatud merereisid: Eestlaste hulljulged põgenemisreisid üle Atlandi 1940.aastate teisel poolel (Forgotten Sea Journeys: The daring escapes of Estonians across the Atlantic in the late 1940s). This book is the only comprehensive account of the modern-day Baltic Viking ships. When it was published in 2010, Mr. Vendla noted that Soviet censorship had suppressed this part of Estonian history and further research was warranted, which this exhibition aims to advance. Please contact lisa.trei@vabamu.ee if you have new information, comments, or corrections.

Refugees today continue to brave the seas, often in unseaworthy and dangerously overcrowded vessels. “Free Winds” is dedicated to all people who have been forced to flee their homes in search of safety and security. It especially honors the refugees of Ukraine who, since the 2022 full-scale Russian invasion of their homeland, have found safe haven in free Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Why did the Baltic refugees leave Sweden?

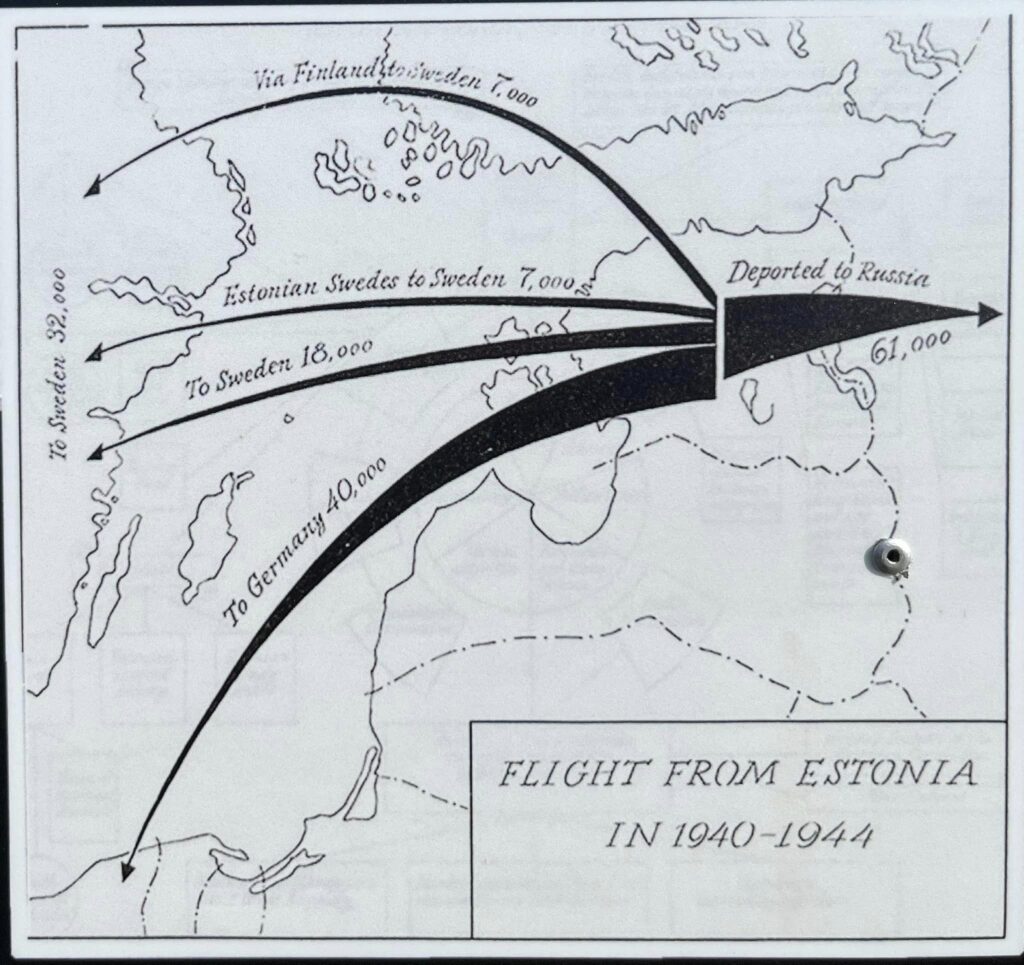

Estonia lost one out of five citizens during World War II. This map shows how 61,000 people were deported, mobilized into the Soviet Army, and voluntarily or forcibly evacuated east. Another 80,000 fled west, mostly to Germany and Sweden.

From 1943 to 1945, about 27,000 Estonians, 4,000 Latvians, and 500 Lithuanians escaped in small boats across the sea to Sweden. About 40,000 Estonians also fled to Germany and 7,000 to Sweden via Finland. Many of the refugees landed in Sweden with only the clothes on their backs. They were placed in relocation camps, given jobs, and were generally well treated by their Swedish hosts. Gradually, they integrated into Swedish society.

Sweden was officially a neutral country during World War II, but in 1940 it recognized the illegal Soviet annexation of the Baltic states. When the Soviet Union reoccupied the region following the collapse of Nazi German rule (1941-44), Soviet officials regarded anyone who had escaped after 1940 to be its citizens and wanted them back.

The Swedish government allowed people working for the Soviet embassy to enter the camps and lead active repatriation campaigns. They distributed pamphlets with titles like, Uuesti kodumaal (Home Again) and Tõde kodumaalt (Truth from the Homeland). These were filled with glowing propaganda about life in Soviet Estonia. Returnees were promised housing, employment, and amnesty if they had worked for the Germans. But following the trauma of Soviet rule during the 1940-41 year of terror, few people believed the propaganda and returned.

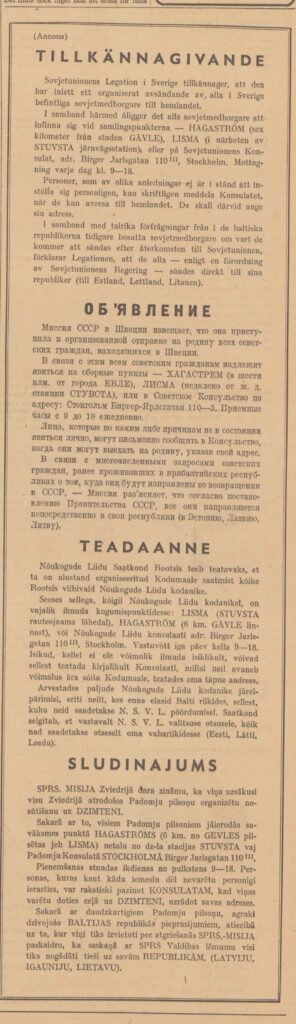

Notice published in Dagens Nyheter on May 20, 1945, announcing that the Soviet embassy in Stockholm has begun organizing the return of “Soviet citizens” from Sweden.

The refugees’ fears deepened when on May 20, 1945, Dagens Nyheter, Sweden’s largest daily, published the following notice about repatriating “Soviet citizens”:

“The Embassy of the Soviet Union in Sweden announces that it has started to organize the return of all Soviet citizens from Sweden.

In connection with this, all citizens of the Soviet Union need to appear at the following collection points: Lisma (near Stuvsta railway station), Hagaström (6 kilometers from the city of Gävle), or at the address of the Soviet consulate: Birger Jarlsgatan 110 III, Stockholm. Reception is held daily from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Individuals unable to appear in person may report in writing to the consulate when they will be able to travel to their home country, providing their address.

Considering the inquiries of many citizens of the Soviet Union, especially from those who had previously lived in the Baltic states, about where they will be sent upon returning to the USSR, the embassy reports that according to the decision of the USSR government, all will be sent directly to their republics (to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania).”

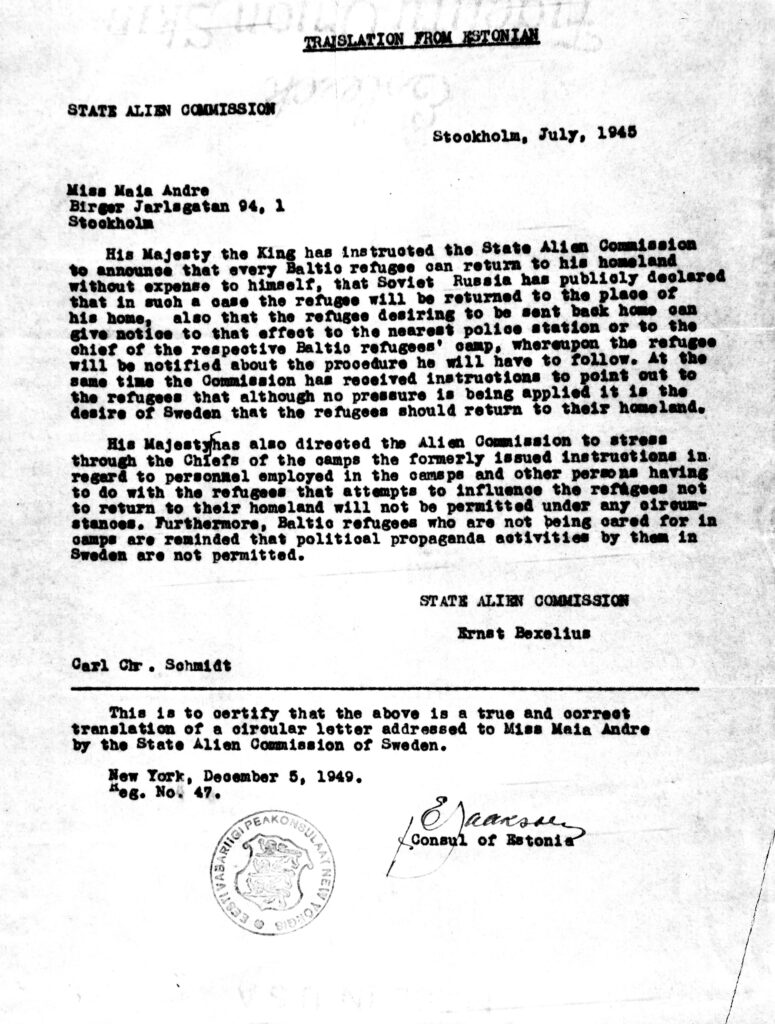

Afterwards, the Swedish State Commission for Foreigners (also State Alien Commission) began sending letters endorsed by the King of Sweden, encouraging the refugees to return. When Maia Andre, a refugee from Käsmu, received a letter in July 1945 (translated into English below), she decided to escape on the Erma.

Extradition of Baltic soldiers — “Baltutlämningen”

A tragic development followed, prompting more refugees to question their safety in Sweden. On January 26, 1946, despite vigorous public protests, the Swedish government handed over to the Soviets 146 Baltic soldiers wearing German army uniforms. The conscripts fled from Latvia to neutral Sweden at the end of war, where they were interned. The Soviets regarded the 130 Latvians, nine Lithuanians, and seven Estonians as traitors. Six of the Estonians had been 16- and 17-year-old boys when they were mobilized on August 20, 1944, into the auxiliary providing ground support to the Deutsche Luftwaffe (German Air Force).

Knowing what awaited them, the conscripts went on hunger strikes, maimed themselves, and even committed suicide. Those forced to board the Beloostrov from Trelleborg, Sweden, to Latvia were later executed, imprisoned, or sent to labor battalions.*

The Swedish Communist newspaper Ny Dag also called for the deportation of all refugees, whom it labeled “Baltic fascists.” Against this backdrop, many understood they needed to get as far away as possible from the Soviet Union—Sweden was too close. For them, it was preferable to risk their lives crossing the oceans in search of freedom than to live in constant fear of being sent back to their occupied homelands.

*On June 20, 1994, 40 of the 44 surviving soldiers—35 Latvians, four Estonians, and one Lithuanian, accepted an invitation to visit Sweden where King Carl Gustaf received them. The Swedish foreign minister, Margaretha af Ugglas, said she regretted the injustice of what had happened but did not apologize. On August 15, 2011, Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt officially apologized to the Baltic prime ministers in Stockholm, referring to the extradition of the conscripts as a “dark moment” in Swedish history.

English translation of the letter Maia Andre received encouraging her to return to Estonia. It is identical to the one sent to Donald Koppel featured in the Estonian version of this exhibition. Fearful they would be extradited to Estonia, Maia fled on the Erma and Donald on the Inanda.